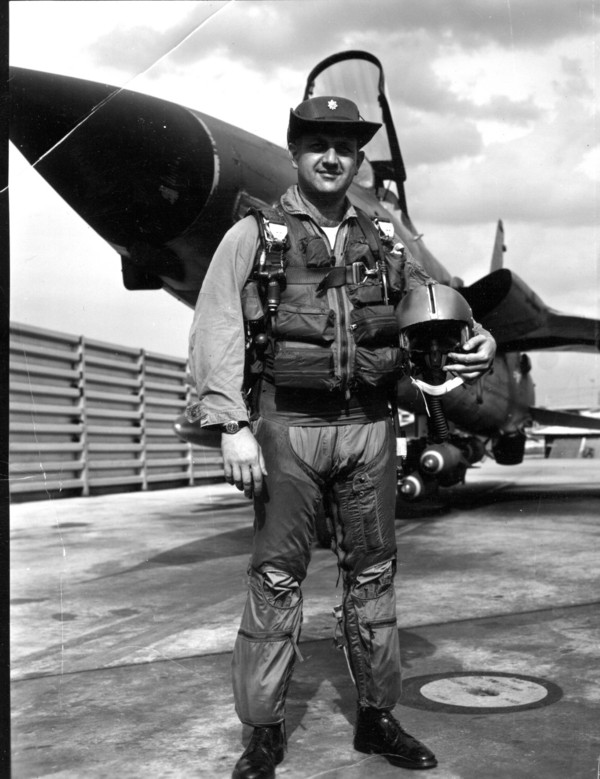

SEYMOUR R BASS - MAJ

- HOMETOWN:

- springfield

- COUNTY:

- Union

- DATE OF BIRTH:

- April 20, 1928

- DATE OF CASUALTY:

- May 14, 1968

- BRANCH OF SERVICE:

- Air Force

- RANK:

- MAJ

- STATUS:

- KIA

- COUNTRY:

- Thailand

Biography

Seymour R. Bass was born on April 20, 1928, to Isidore and Mamie Bass, who immigrated to the United States from the Ukraine. His home of record is Springfield, NJ. He had one sister, Lillian, and two brothers, William and Daniel. Seymour attended Dover High School in Dover, NJ, and graduated in 1946. He enjoyed all types of music, especially classical and folk, and he played the clarinet, saxophone and flute. You could also find him bicycle riding, gardening and talking politics.

Bass continued his education and received a degree from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in 1950. In 1964, he received a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of New Hampshire in Electrical Engineering.

Seymour and his wife, Lillian, had two children, Carol Ann and Harvey.

He enlisted in the US Air Force and attained the rank of Major (MAJ).

Bass was killed in action on May 14, 1968. He was buried at Dover Military Cemetery in Dover, NJ. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The following was written by Carol Ann Bass, the daughter of Seymour R. Bass, and appeared in the New York Times on May 29, 1988.

While all war memorials list the names of those who died, or who fought in a conflict, I have never heard of a structure for any war commemorating families of the deceased. Surely their suffering was almost as great as that of those who gave their lives or saw combat. I know because I belonged to one of those forgotten families.

Growing up in a small New England town similar to the one I live in now, I never saw a battle except on television, never saw a gun except in the museum and never really cared what my father did for a living. Until 1968.

That year, a month after my 13th birthday, my father was killed in a military jet over Thailand. He was 39 years old. To all my school friends at the time, and for many years to come, Vietnam was a place far away, a story on television, a topic for rock songs and a pivotal issue on which a generation could focus its anger and its fear of growing up.

For my mother, my brother and me, Vietnam was a real place that would damage our lives forever.

The summer before my father left, I asked him why we never put a flag in front of our house on Independence Day, like many of out neighbors did. His answer foretold what we would endure.

"We don't need one," he said. "My life is serving our country. I wear the flag on my heart every day." It was not until the chaplain handed the flag to my mother at my father's funeral that I understood what he meant.

Because of his sacrifice, I lost my last years of childhood and much joy after that. While most girls in junior high school were thinking about clothes and boys, I relived the memory of a rainy day in November when my father drove me to school. He held me tightly and said goodbye, with both of us knowing we might never see each other again.

I remember people joking weeks later about the shape of the negotiating table at the peace talks in Paris. "Please," I prayed, "Hurry up." For my father, peace came too late.

In high school, I never went to a party because rock music was often anti-war and it mocked what my father had done. I had nothing in common with classmates whose worst problems were convincing their parents to let them stay out later. I would have given anything for a father to tell me when to come home!

Instead of turning toward life and the adventures of youth, I spent those years in my room reading. My father had remodeled it just before he left, and it was there I felt safe from the war, the 60's generation and the pain and conflict, which pitted me in the middle.

Later, in college, I found myself defending my father's actions in dormitory discussions as well as in political science courses. European exchange students became my best friends because they saw what war had done to their homeland and to the lives of their parents and grandparents.

My father's death left us with little money. Many things I would have had if he were alive I did without. I felt the strain so keenly that I chose a career in business to recapture a sense of financial stability. Since that profession was ill-suited to my temperament or talents, I have not yet experienced the satisfaction of a rewarding career.

At my wedding, there was no one to give me away. At the birth of my sons, I could not see that special joy of their grandfather. It is going to be so difficult to tell them someday why they will never see their mother's daddy. I want my boys to grow up with the same qualities he had, but maybe that would mean they, too, would become soldiers and, perhaps, die. As a daughter, I barely survived the loss. As a mother, I am not sure if I could.

Those who died in the Vietnam War deserve the appreciation of this country for making such a sacrifice. They deserve the recognition of a monument. But those families that experienced the horror of war back in the Untied States deserve something, too.

Maybe not a monument. There are too many of us for that. Maybe we should just be remembered in the prayers of Americans on this and future Memorial Days.

Sources: Carol Ann Bass (daughter) and NJVVMF.

Remembrances

Be the first to add a remembrance for SEYMOUR R BASS

Help preserve the legacy of this hero, learn about The Education Center.

LEARN MORE